The prairie regions of central Asia and North America, rainforests in Central America and South America, and eastern Australia all have one thing in common: They are among the most sensitive land ecosystems on Earth when it comes to climate change.

That’s according to new research published in the journal Nature on Wednesday that identified where around the world vegetation has responded most to climate fluctuations.

“What this approach now enables us to to do is to start to identify the most vulnerable natural capital stocks provided by vegetation,” Dr. Kathy Willis, the director of science at the U.K.’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and a co-author of the study, told The Huffington Post, “and this in itself provides an important first step to highlight regions of sensitivity, and conversely resilience, for global food security and other important resources that we obtain from plants.”

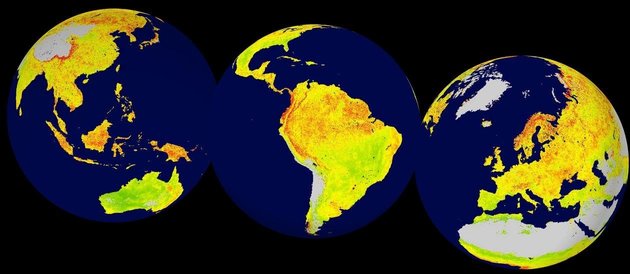

The research team created a map (below) of these vulnerable ecosystems in an effort to help scientists better visualize how climate change may impact our planet’s future, Dr. Alistair Seddon, a researcher in the department of biology at the University of Bergen in Norway and lead author of the new study, told The Huffington Post.

“Now we have this global picture, it can guide the next areas of research,” he said. “Ecosystems are likely going to have to face multiple dimensions of climate change in the future — increases in average temperatures, no-analogue conditions — but understanding how they will respond to variability is also a key knowledge gap.”

The researchers used satellite data from 2000 to 2013 to examine how various ecosystems responded to monthly changes in climate over time.

They then used the data to devise a so-called Vegetation Sensitivity Index, which compares fluctuations in temperature, water availability and cloudiness to the health of plants in a certain ecosystem.

As the research focused solely on how plants responded to changes in climate, Seddon told HuffPost that more research is needed to explore how such sensitivity might impact human populations.

The Washington Post reported that Dr. Thomas Lovejoy, an ecologist at George Mason University in Virginia who was not involved in the study, called the new study “an important advance.”

“But it is by definition an underestimate of sensitivity because biological interactions (like bark beetles in coniferous forests and bleaching events in corals) show major ecosystem impacts can occur on top of and as part of vegetation or ecosystem impacts,” Lovejoy told the newspaper. “All the more reason to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees.”

By Huffington Post